The S.S. Andaste

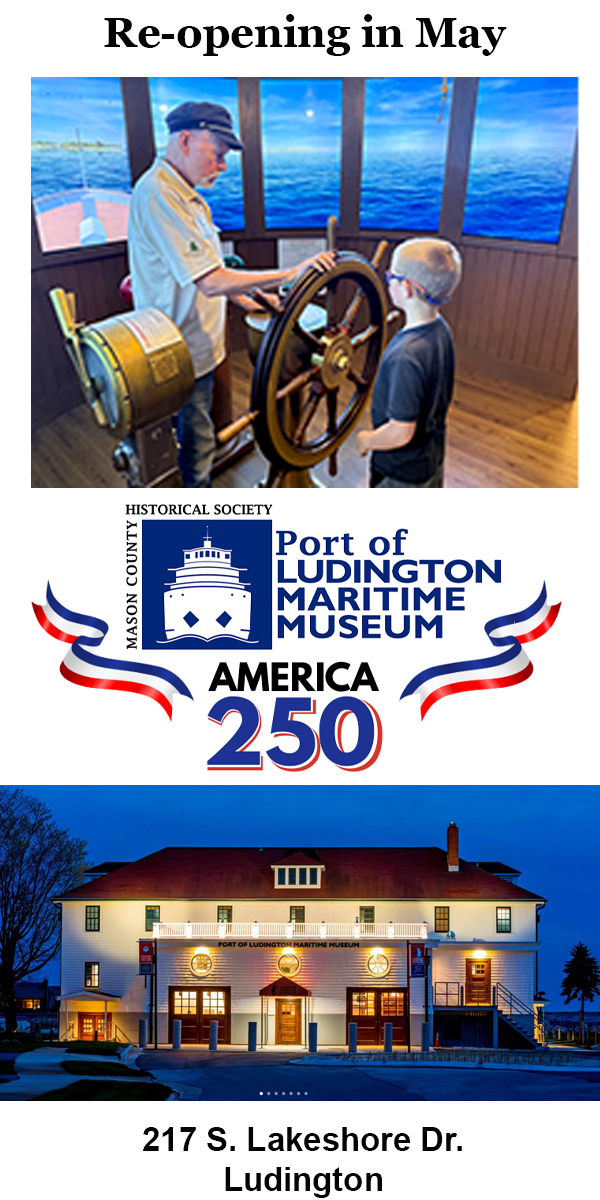

Great Lakes History Log is presented by Filer Credit Union with offices in Manistee, Ludington, East Lake, and Bear Lake and the Mason County Historical Society, which operates the Port of Ludington Maritime Museum, Historic White Pine Village and the Rose Hawley Archives in downtown Ludington.

Part 1: S.S. Andaste

By Rob Alway, Editor-in-Chief

The last four months of 1929 were a deadly time for Lake Michigan shipping. At least four shipwrecks claimed the lives of over 100 people. This series will discuss each of those wrecks and will also make some comparisons to why some resulted in total losses while others had much fewer lives lost.

The ships lost included the S.S. Andaste (Sept. 9), the S.S. Milwaukee (Oct. 22), the S.S. Wisconsin (Oct. 29), and the S.S. Senator (Oct. 31). Of those five wrecks, two of them resulted in total lives lost. Neither of those two ships, the Andaste and the Milwaukee, were equipped with wireless radio.

Read about the sinking of the Milwaukee in part 2 of this series here.

Read about the sinking of the Wisconsin in part 3 of this series here.

The Andaste was a Monitor-class ship built by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Co. of Lorain, Ohio, and launched on March 31, 1892. It was originally built for the Lake Superior Iron Company but the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company became its owner following Lake Superior Iron Company’s bankruptcy in 1898.

It was 266.9 feet long, 38.1 feet wide and 17.9 feet deep. The ship had a cutaway stern, seven deck hatches, and no interior bulkheads between the forward collision bulkhead and the engine bulkhead in the rear. It could carry 2,800 short tons fully loaded.

The Cleveland Shipbuilding Co. began in 1888. It changed its name to American Ship Building Company in 1900 when it acquired Superior Shipbuilding of Superior, Wis., Toledo Shipbuilding of Toledo, and West Bay Shipbuilding of West Bay City, Mich.

The Andaste was one of the company’s first ships to be built, according to records. Andaste is a French name for the Susquehannock people. Its sister ship, the S.S. Choctaw — named after the Choctaw people — was also built in 1892. It sank on July 11, 1915 on Lake Huron with all 22 crew saved. The two ships had an unusual design. They were straight-back steel freighters, similar to the popular whalebacks, but they had straight sides and a conventional bow. The combination meant that from the waterline upward, their sides sloped inboard in a “tumble-home” configuration. They were also known as “semi whalebacks.” Like the whalebacks, they were vulnerable to getting a wet deck in a storm or gale conditions.

In the winter of 1920-1921 the vessel was shortened from 266 feet to 246 feet by the Great Lakes Engineering Works in Ecorse, Mich. By shortening the vessel it was able to navigate in the Welland Canal and the St. Lawrence River.

The Great Lakes Engineering Works operated between 1902 and 1960. Within three years of its formation, it was building 50 percent of the tonnage of all ships on the Great Lakes. It is best known as the builder of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald and as the innovator of the first self-unloading freighter, the S.S. Wyandotte. In 1961, the company dissolved with its assets sold to Great Lakes Steel Corp.

In 1898, the two ships were transferred from Lake Superior Iron to the Cleveland Cliffs Co. They carried coal, iron ore and grain from Lake Superior to the lower Great Lakes.

The Andaste under way.

In 1925, the ship had been purchased by the Cliffs-L.D. Smith Steamship Company and was refitted again at Sturgeon Bay, Wis., allowing for the ship to transport crushed stone and stone aggregate. A self-unloading crane was refitted onto the boat’s hull and frame. Its new Leatham Smith tunnel scrapers were intended to enable the ship to unload more quickly and to partially offload at ports that could not previously be serviced by a bulk carrier.

Leatham Smith operated a quarry in Sturgeon Bay, Wis. In 1920, he patented the tunnel scraper system in an effort to make shipping of rock from the quarry to Chicago more efficient. The new system shortened the time required to unload a giant cargo ship from two or three days to just hours, and the scraper system took up less room than previous equipment, increasing cargo space. The invention developed into a L.D. Smith Shipbuilding in Sturgeon Bay which ultimately produced 85 vessels. The company eventually became Christy Corporation (which build the S.S. Spartan and S.S. Badger carferries) in 1944. The site of the original shipyards is now home of Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding Co.

Although the self-unloading apparatus on the Andaste made economic sense, the topside gear apparently had negative effects upon the metacentric stability of the vessels that took on the new machinery. Four of the refitted ships were lost in relatively quick progression. Metacentric stability is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body.

On Sept. 9, 1929, the Andaste was taking on a 2,000 ton load of aggregate from a glacier-deposited mound of sand and gravel located where the small Bass River meets the Grand River, 12 miles southeast of Grand Haven. The area, located in Robinson and Allendale townships, is now the 1,665-acre Bass River State Recreation Area, owned by the State of Michigan and operated by Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

The Andaste was under the command of Capt. Albert L. Anderson (1866-1929) of Sturgeon Bay, who had 40 years sailing experience, 30 as a licensed captain. Anderson was born on Oct. 28, 1866. He had grown up in Sturgeon Bay and graduated from high school there. At the age of 32, he married Georgiana Remellard, according to his obituary, published Sept. 20, 1929 in the Green Bay Press-Gazette. The two had one daughter, Madonna, and two sons, Merle and John, who all lived in Sturgeon Bay at the time of his death. Another son, Clifford, is listed in a family tree on Ancestry.com, likely having died in infancy. Anderson is buried at Bayside Cemetery in Sturgeon Bay.

Late that evening the Andaste cast off and headed downstream to Lake Michigan, en route to Chicago. The U.S. Coast Guard logged it as passing through the Grand Haven pier heads at 9:03 p.m., the last verified sighting of the vessel.

An hour after Andaste departed Grand Haven, a stiff wind sprang up. Gale warnings were posted but the ship had no way of knowing as it did not have a radio. The storm continued to developing, producing 60 mph winds by 1 a.m. on Sept. 10. The vessel failed to show up in Chicago.

Searches for the Andaste immediately began on Sept. 11. On Sept. 12, wreckage was discovered floating southwest of Holland. The wreckage included a cabin door and hatch strongbacks that were identified by a former Andaste crewman. Hatch strongbacks are structural components used to reinforce hatch covers on boats and ships, ensuring a watertight seal and providing structural support. They are often used in conjunction with hatch covers to prevent them from bending or collapsing under pressure, particularly in rough seas.

By Sept. 13, the Associated Press was reporting the wreckage to be that of the Andaste.

The bodies of 16 of the 25 men aboard were eventually recovered; 11 of the 16 were wearing life jackets. Among the missing crewmen was Earl Zietlow, 14, who was a steward’s assistance on his first voyage.

Later, men searching the Ottawa County beaches for bodies found a bobbing, splintered plank or piece of board siding. On the wood was written, with pencil, a note: “Worst storm I have ever been in. Can’t stay up much longer. Hope to God we are saved. A.L.A.,” the initials of Capt. Anderson.

A coroner’s jury was summoned to investigate the cause of the sinking. A coroner’s jury was a group of citizens who were summoned to serve as members of an inquest to determine the cause of any accidental or suspicious death that occurred within a specific jurisdiction. The coroner’s jury could also be called upon to determine the identity of a deceased person. In this case of the Andaste’s coroner’s jury, the members were all Holland businessmen who had an interest in Lake Michigan safety.

The condition of the vessel prior to its foundering was a point of concern for the jury. The life-jacketed corpses that washed ashore were seen by some as a sign that the doomed vessel had fallen into what is called the “trough” of the gale waves. This is a condition when a vessel, often with impaired metacentric functions, cannot recover after being hit broadside by a breaking wave. Partly swamped, the rolling vessel falls down in the wave troughs and does not rise with the wave crests.

Questions were raised at the jury’s inquiry about the metacentric stability of the Andaste with its topside self-unloading machinery. Great Lakes seamen were aware that a structurally similar (although not identical) aggregate freighter, the Clifton, had been refitted with similar topside self-unloading machinery and had disappeared with all hands on Lake Huron in September 1924. A similar retrofit and sinking involved the Hennepin when it sank west of South Haven on Aug. 18, 1927.

The corpse of First Mate Charles Brown was found wearing high rubber boots, which was a sign that the vessel was prone to shifting its cargo of aggregate in bad weather and that the officer may have had to dress himself for the frantic task of shoveling gravel uphill inside a wet ship’s hold. However, there was no way to confirm or deny this speculation.

The jury issued three recommendations:

- All large vessels operating on the Great Lakes be equipped with a radio apparatus

- Five central marine offices be established, one for each of the Great Lakes, to officially report missing vessels.

- Proper facilities be maintained on each of the five Great Lakes for immediate searches and rescues.

While this series focuses on four shipwrecks that occurred in the later half of 1929, three of those four occurred as a result of rough seas while the fourth, the sinking of the Senator, was the result of a collision attributed to fog. Of the other three, the Andaste and the Milwaukee were not equipped with wireless radio while the Wisconsin did feature the technology. As a result, the Wisconsin was able to request assistance, which ultimately meant the saving of lives. All were lost on the other two vessels.

Wireless communication in the maritime industry began in 1899 with the first ship-to-shore wireless message sent to a U.S. station. This initial communication, using wireless telegraphy, paved the way for wider adoption of wireless technology in the maritime industry. The use of wireless telegraphy expanded rapidly, with the first transatlantic wireless message being sent in 1901.

Wireless communication was attributed to the saving of many lives when the Pere Marquette Railway car ferry, S.S. Pere Marquette 18, which sank on Sept. 10, 1910. The captain was able to request aid, which was rendered by the vessel’s sister ship, the Pere Marquette 17. It was the policy of the Pere Marquette Railway, since 1909, to equip its carferry fleet with radios. Stephen F. Sczepanek, purser and wireless operator of the PM 18, is credited as being the first mariner on the Great Lakes to send a CQD distress signal (prior to “SOS”) and thus, save many lives. This occurred two years before the sinking of the RMS Titanic in the North Atlantic Ocean.

To date, the wreck of the Andaste has not yet been located.

The Mason County Historical Society is a non-profit charitable organization that was founded in 1937 that does not receive any governmental funding. It owns and operates the Port of Ludington Maritime Museum in Ludington, Historic White Pine Village in Pere Marquette Township, and The Rose Hawley Archives and the Mason County Emporium and Sweet Shop in downtown Ludington.

For more information about donating to and/or joining the Mason County Historical Society, visit masoncountymihistory.org.

_______________________

Please Support Local News

Receive daily MCP and OCP news briefings along with email news alerts for $10 a month. Your contribution will help us to continue to provide you with free local news.

To sign up, email editor@mediagroup31.com. In the subject line write: Subscription. Please supply your name, email address, mailing address, and phone number (indicate cell phone). We will not share your information with any outside sources. For more than one email address in a household, the cost is $15 per month per email address.

We can send you an invoice for a yearly payment of $120, which you can conveniently pay online or by check. If you are interested in this method, please email editor@mediagroup31.com and we can sign you up. You can also mail a yearly check for $120 to Media Group 31, PO Box 21, Scottville, MI 49454 (please include your email address).

Payment must be made in advance prior to subscription activation.

We appreciate all our readers regardless of whether they choose to continue to access our service for free or with a monthly financial support.

_____

This story and original photography are copyrighted © 2025, all rights reserved by Media Group 31, LLC, PO Box 21, Scottville, MI 49454. No portion of this story or images may be reproduced in any way, including print or broadcast, without expressed written consent.

As the services of Media Group 31, LLC are news services, the information posted within the sites are archivable for public record and historical posterity. For this reason it is the policy and practice of this company to not delete postings. It is the editor’s discretion to update or edit a story when/if new information becomes available. This may be done by editing the posted story or posting a new “follow-up” story. Media Group 31, LLC or any of its agents have the right to make any changes to this policy. Refer to Use Policy for more information.

.png)